Celebrating Black History Month: Black Innovators, Intellectual Property, and the Fight for Recognition

Black Americans have made tremendous contributions to music, technology, and more, but many have faced significant challenges in securing protection and recognition for their work. In honor of Black History Month, we briefly explore some of these historical barriers to intellectual property protection, allowing us to gain a deeper appreciation for the impact Black creators and inventors have had, and continue to have, on our world.

Exploitation of Black Musicians

The evolution of American music cannot be completely understood without acknowledging the profound influence of Black musicians. Genres like jazz, blues, rock ‘n’ roll, and hip-hop owe their origins to Black artists who infused their experiences and stories into their art. Despite that, many of these artists have faced significant hurdles in protecting and profiting from their creations.

Throughout the early-to mid-20th century, Black musicians were frequently hired by white-owned record labels under work-for-hire contracts, or were otherwise paid a flat-fee for their musical contributions. These arrangements allowed record labels to retain exclusive copyright ownership of the creations of these Black artists.

In the 1950s, record labels discovered the lucrativeness of offering compulsory licenses to white artists who wished to cover songs originally written and performed by Black musicians, and these covers frequently outsold the originals. However, due to the work-for-hire or flat-fee arrangements, the Black creators behind these songs were not entitled to any of the royalties stemming from the success of these cover records.

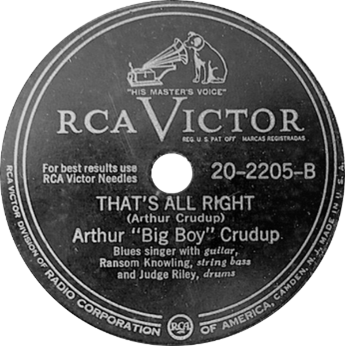

A prime example of this practice can be seen in the experience of Black blues musician Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup who wrote the song That’s All Right, Mama, later popularized by Elvis Presley. Even though over 100,000 copies of Presley’s cover record were sold, Crudup did not receive any royalties from the success of his song because his producer owned the song’s copyright. In fact, Crudup had to supplement his earnings as a musician by working as a field laborer, and ultimately left the music industry due to lack of compensation. Eventually, Crudup received a modest royalty payment of $1,600, but his producer refused to relinquish the copyright. It wasn’t until after Crudup’s death that his estate began receiving royalties for Presley’s rendition of That’s All Right, Mama, underscoring the systemic exploitation faced by Black musicians, where recognition and financial compensation were often delayed or denied during their lifetimes.

A prime example of this practice can be seen in the experience of Black blues musician Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup who wrote the song That’s All Right, Mama, later popularized by Elvis Presley. Even though over 100,000 copies of Presley’s cover record were sold, Crudup did not receive any royalties from the success of his song because his producer owned the song’s copyright. In fact, Crudup had to supplement his earnings as a musician by working as a field laborer, and ultimately left the music industry due to lack of compensation. Eventually, Crudup received a modest royalty payment of $1,600, but his producer refused to relinquish the copyright. It wasn’t until after Crudup’s death that his estate began receiving royalties for Presley’s rendition of That’s All Right, Mama, underscoring the systemic exploitation faced by Black musicians, where recognition and financial compensation were often delayed or denied during their lifetimes.

Obstacles to Black Inventorship

The realm of invention tells a similar story. Black inventors have been responsible for groundbreaking innovations, yet systemic barriers have often prevented them from securing patent protection, profiting from their work, or receiving due recognition for their inventions.

Enslaved people were legally barred from owning property, which included intellectual property. Their inventions, if acknowledged at all, were left unprotected. For example, in 1857, Oscar J.E. Stuart, a lawyer and enslaver from Mississippi, attempted to patent a plow invented by his enslaved worker, Ned. The U.S. Patent Office rejected Stuart's application, stating that Ned, as an enslaved person, was ineligible to take the inventor’s oath, and Stuart, who did not devise the invention, could not claim to be the inventor just by virtue of being Ned’s enslaver.

Although emancipation eliminated the codified barriers that prevented Black inventors from acquiring patent protection for their invention, institutional racism ensured that these obstacles persisted.

One such inventor who faced these sorts of difficulties was Granville T. Woods, ironically known as the “Black Edison.” A mechanical and electrical engineer responsible for major developments in railway technology, Woods managed to secure over 50 patents in his lifetime. However, Woods spent much of his time and nearly all of his money defending his work against legal claims from white inventors, including Thomas Edison, who attempted to take credit for his work. Although Woods succeeded in many of these battles for recognition, he struggled to market and profit from his inventions. He ended up selling several patents to buyers such as General Electric and even Thomas Edison for significantly less than their true value, and in doing so, lost his claim to these inventions as well as his right to any profits. Despite his undeniable impact in transportation technology, Woods died destitute, exemplifying the institutional racism that kept Black inventors from fully reaping the rewards of their ingenuity.

One such inventor who faced these sorts of difficulties was Granville T. Woods, ironically known as the “Black Edison.” A mechanical and electrical engineer responsible for major developments in railway technology, Woods managed to secure over 50 patents in his lifetime. However, Woods spent much of his time and nearly all of his money defending his work against legal claims from white inventors, including Thomas Edison, who attempted to take credit for his work. Although Woods succeeded in many of these battles for recognition, he struggled to market and profit from his inventions. He ended up selling several patents to buyers such as General Electric and even Thomas Edison for significantly less than their true value, and in doing so, lost his claim to these inventions as well as his right to any profits. Despite his undeniable impact in transportation technology, Woods died destitute, exemplifying the institutional racism that kept Black inventors from fully reaping the rewards of their ingenuity.

Conclusion

Despite the historical obstacles faced by Black innovators seeking to protect and profit from their intellectual property, their contributions have left an indelible mark on history.

This Black History Month, we celebrate their remarkable contributions while also recognizing the barriers they've had to overcome to safeguard and receive recognition for their work.

Sources:

- Candace G. Hines, Black Musical Traditions and Copyright Law: Historical Tensions, 10 Mich. J. Race & L. 463 (2005).

- https://www.elvisthemusic.com/music/thats-all-right/

- https://www.pbs.org/newshour/arts/he-wrote-elvis-first-hit-but-arthur-crudup-barely-got-paid

- Olivia C. Bethea, The Unmaking of the “Black Bill Gates”: How the U.S. Patent System Failed African-American Inventors, U. Pa. L. Rev. 170:17 (2021).

- https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/resources/landslide/archive/colorblind-patent-system-black-inventors/

- https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/for-black-inventors-road-to-owning-patents-paved-with-barriers

- https://www.businessinsider.com/granville-woods-black-inventor-thomas-edison-electricity-invention-telegraph-2023-11

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/obituaries/granville-t-woods-overlooked.html

For further information, please contact Avanthi M. Cole or your CLL attorney.

Associate

Email | 212.790.9267

Avanthi’s practice specializes in intellectual property disputes, with a focus on copyright and trademark litigation and counseling. She has represented clients across a range of industries, including social media platforms, pharmaceutical companies, online businesses, and domain name registrars.